Adventure

And where to find it.

Last Wednesday Molly and I and a few friends boated to Angel Island (San Francisco bay, north of Alcatraz) to camp for the night.

On a sunset-turned-night hike up the island’s humble summit I was talking to Rob about the time he and some friends donned skis and sleds, roped up together, and walked four miles across the frozen crust of Lake Superior to spend an uncomfortable -11 degree (-24C) night packed into Rabbit Island’s only heated shelter—a small sauna with an unfortunate amount of airflow through its floorboards.

He said the best part of the excursion “was the shared uncertainty.”

That resonated and got me thinking about how I value and define adventure. It also made me want to engage in a little adventure advocacy.

There’s Adventure with a capital “A”, of course. Shackleton's trip down South. Losing your whaling ship. Floating the uncharted Colorado. Traversing forgotten coastline. Swimming herculean distances.

But, adventure comes in sizes big and small. Personal thresholds vary, and great unknowns are harder and harder to come by. So, micro-adventures count just the same.

Actual requirements are few: Novelty. Uncertainty. Maybe some discomfort. Think pitching a pup tent in the backyard as a kid. Backpacking as an adult. Exploring the backcountry in a vehicle. Traveling abroad. Setting sail for an island… or walking to it.

To me it’s more perspective than the actual risk of the undertaking. The anticipatory energy of the new, and the shared excitement of experiencing the uncertain. Gearing up. Training. Preparations and planning. Thinking through the lens of self-reliance and reliance on your partners.

I see overlap with some of our building projects. Projects in general, really. There are trials and tribulations. Unknowns and the inevitable problem-solving. It’s communal, and the only way it’s getting figured out and finished, is by the folks you’re with and the resources you’ve got.

One of the reasons that I find myself so enamored of Lloyd Kahn (who is now on Substack) is that even into old age he retains a zeal for unfamiliar experiences.

Voluntarily subjecting yourself to discomfort and stoking those flames of curiosity seems a hard ask as the years tick by. A muscle that would atrophy otherwise. Lloyd is a beacon.

Adventure is the chance for things to go wrong. In fact, it’s possibly better if it goes a bit wrong and things get a little rough.

A good-time-gone-awry is a chance for some Type 2 Fun—that brand of fun that’s not all that enjoyable in the moment and leaves you pining for the sofa back home.

Those hard-won experiences are bonding and the memories lasting. Recollections of folly and hardship, years at the ready and shared through laughter, are the hallmarks of an adventure.

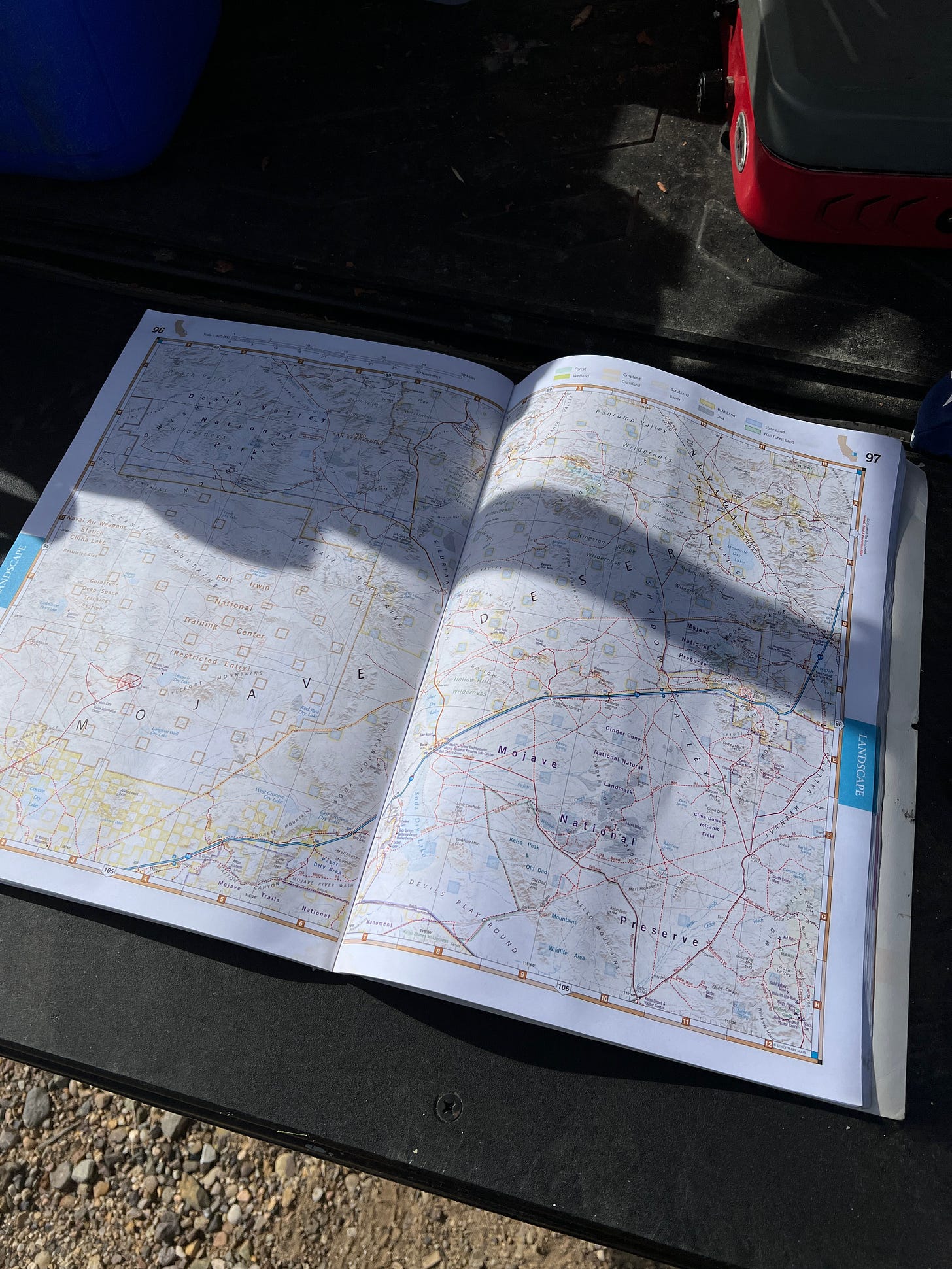

One of those instances that recently came up in conversation: Last year Molly and I took a shortcut (that was anything but) across a good chunk of the Mojave desert, and it stands as the most revisited memory of that trip. (Perhaps in part, because the full story of this detour starts with locating a roadkill roadrunner and ends with my finger getting stitched back together at our kitchen table.)

We didn’t take any photos, given the waning excitement and her understandably tested patience for my dead-bird decision-making, but there are moments of that drive that stand out to both of us as some of the most beautiful of the journey.

All that’s to say, a wrong turn could ruin an experience, or it can become the most memorable part.

Big or small, it’s perspective. A Raymond Chandler line I draw on often: “...it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure.”